With global chronic undernourishment now on a downward trend, the world is beginning to turn a corner in its fight against hunger. The United Nations’ newly released The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 reports that 673 million people (8.2% of the world’s population) were undernourished in 2024. This is down from 688 million in 2023. Although we have not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels (7.3% in 2018), this reversal marks a welcome shift from the sharp rise experienced during COVID-19.

India has played a decisive role in this global progress. The gains are the result of policy investments in food security and nutrition, increasingly driven by digital technology, smarter governance, and improved service delivery.

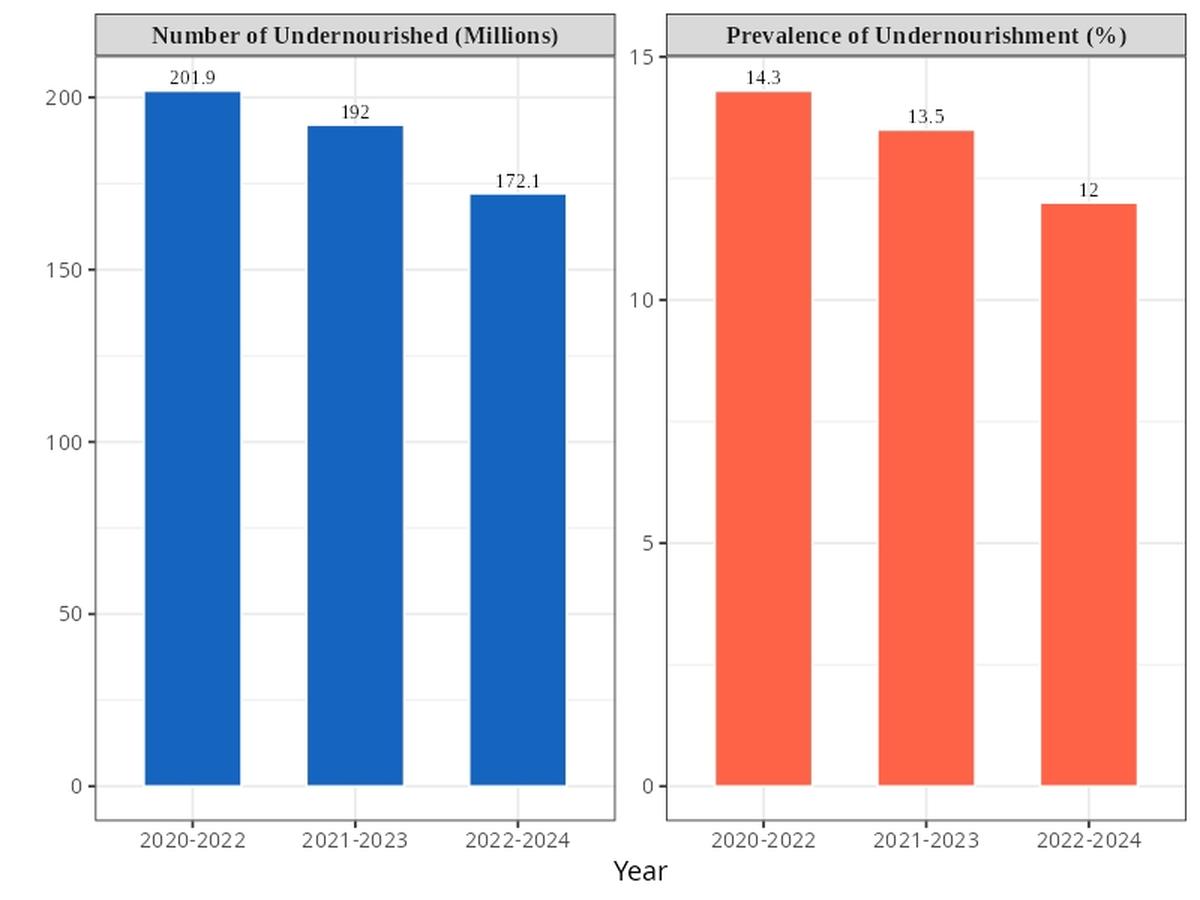

Revised estimates using the latest National Sample Survey data on household consumption show that the prevalence of undernourishment in India declined from 14.3% in 2020–22 to 12% in 2022–24. In absolute terms, this means 30 million fewer people living with hunger — an impressive achievement considering the scale of the population and the depth of disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The transformation of the PDS

At the centre of this progress is India’s Public Distribution System, which has undergone a profound transformation. The system has been revitalised through digitalisation, Aadhaar-enabled targeting, real-time inventory tracking, and biometric authentication. The rollout of electronic point-of-sale systems and the One Nation One Ration Card platform have made entitlements portable across the country, which is particularly crucial for internal migrants and vulnerable households.

These innovations allowed India to rapidly scale up food support during the pandemic and to continue to ensure access to subsidised staples for more than 800 million people.

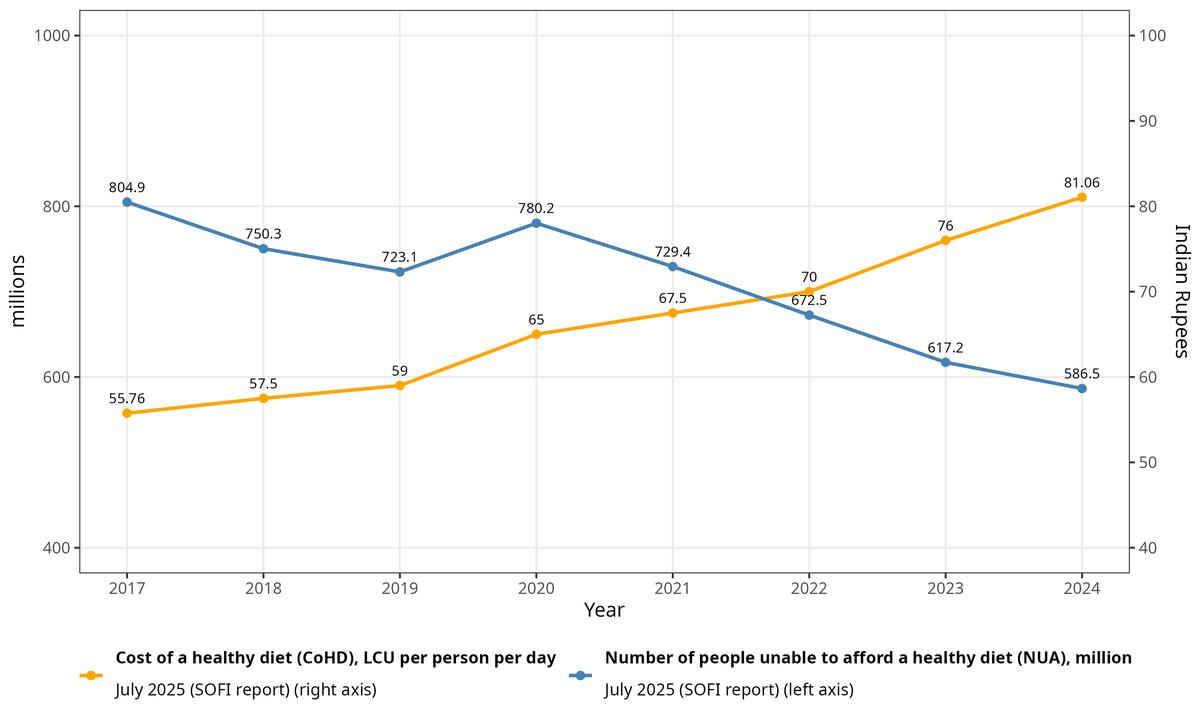

Now, progress on calories must give way to progress on nutrition. The cost of a healthy diet in India remains unaffordable for over 60% of the population, driven by high prices of nutrient-dense foods, inadequate cold chains, and inefficient market linkages. That said, India has begun investing in improving the quality of calories. For example, the Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman (PM POSHAN) school-feeding scheme, launched in 2021, and the Integrated Child Development Services are now focusing on dietary diversity and nutrition sensitivity, laying the foundation for long-term improvements in child development and public health.

New data in the UN report also shows progress the country has made in making healthy diets more affordable despite food inflation.

What is happening underscores a larger structural challenge: even as hunger falls, malnutrition, obesity, and micronutrient deficiencies are rising. This is especially so among poor urban and rural populations.

The agrifood system needs transformation

India can meet this challenge by transforming its agrifood system. This means boosting the production and the affordability of nutrient-rich foods such as pulses, fruits, vegetables, and animal-source products, which are often out of reach for low-income families. It also means investing in post-harvest infrastructure such as cold storage and digital logistics systems, to reduce the estimated 13% of food lost between farm and market. These losses directly affect food availability and affordability.

In addition, India should further strengthen support for women-led food enterprises and local cooperatives, including Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), especially those cultivating climate-resilient crops, as these can enhance both nutrition and livelihoods.

India must continue to invest in its digital advantage to drive the transformation of its agrifood systems. Platforms such as AgriStack, e-NAM, and geospatial data tools can strengthen market access, improve agricultural planning, and enhance the delivery of nutrition-sensitive interventions.

A symbol of hope

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) notes that the progress of India in agrifood system transformation is not just national imperatives; they are global contributions. As a leader among developing countries, India is well-positioned to share its innovations in digital governance, social protection, and data-driven agriculture with others across the Global South. India’s experience shows that reducing hunger is not only possible but that it can be scaled when backed by political will, smart investment, and inclusion.

With just five years left to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) on ending hunger, India’s recent performance gives this writer hope. But sustaining this momentum will require a shift from delivering sustenance to delivering nutrition, resilience, and opportunity.

The hunger clock is ticking. India is no longer just feeding itself. The path to ending global hunger runs through India, and its continued leadership is essential to getting us there.

Maximo Torero Cullen is Chief Economist, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Published – August 19, 2025 12:08 am IST