‘Currently, the scope of the Bilateral Trade Agreement is unclear’

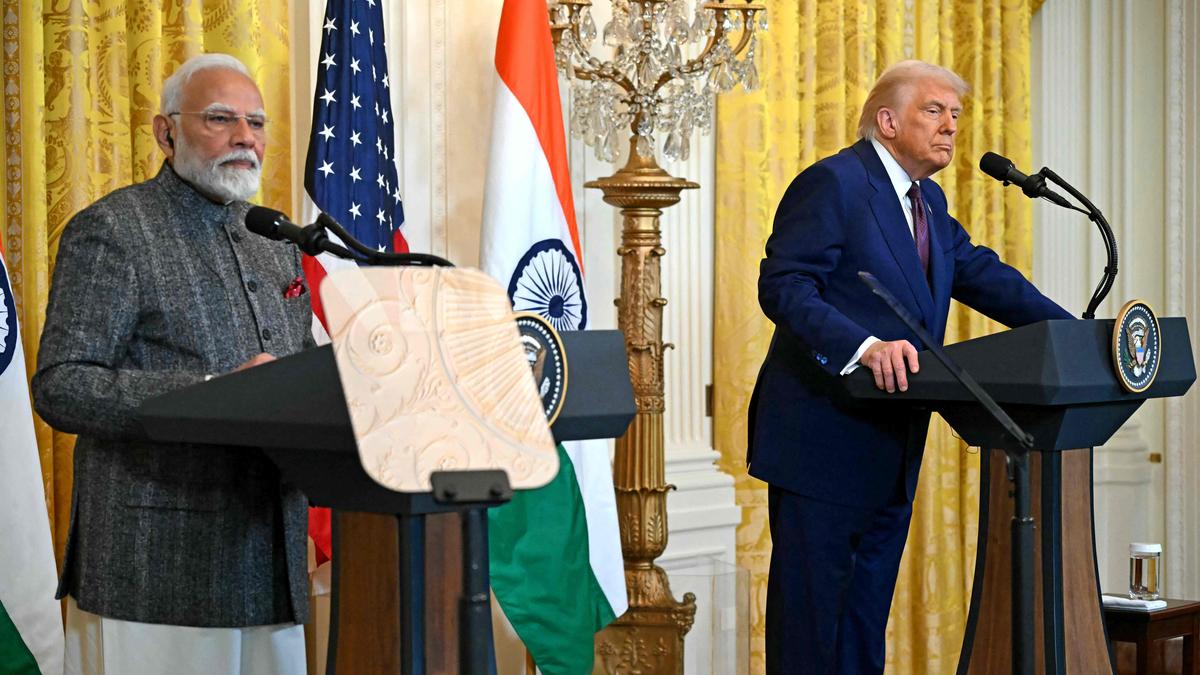

| Photo Credit: AFP

During Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s brief working visit to the United States, on February 13, 2025, New Delhi and Washington agreed to negotiate the first stage of a mutually beneficial, multi-sector Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) by the fall of 2025. While economists are busy calculating tariffs and trade volumes, it is essential to examine this development through the lens of international trade law. A significant portion of international trade law is codified in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and governed by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Since both the U.S. and India are members of the WTO, their bilateral trade dealings must align with the standards set by WTO law. This makes the proposed BTA between the two countries particularly important. Currently, the scope of the BTA is unclear. The U.S.-India Joint Leaders Statement, of February 13, only references a multi-sector BTA without providing specific details about its coverage. It is important to note that this agreement is not labelled as a free trade agreement (FTA). However, the terminology is less significant than the actual content of the agreement.

Free trade agreements

The WTO system operates on the most favoured nation (MFN) principle, which prohibits discrimination between trading partners. Therefore, an FTA that grants preferential access to certain countries violates the MFN rule, although countries can still establish FTAs under specific conditions.

One of these conditions, outlined in Article XXIV.8(b) of the GATT, requires member countries to eliminate customs duties and other trade barriers on “substantially all the trade” within the FTA. Although the term “substantially all the trade” is not defined in the agreement, it is understood that the FTA should encompass a very high percentage of trade between the member countries.

This requirement exists because FTAs are exceptions to the MFN principle, which is a cornerstone of the multilateral trading system. Therefore, these exceptions must be tightly controlled and not permitted lightly. The proposed BTA between India and the U.S. must cover “substantially all trade” to be legally valid. It also needs to be notified to the WTO. Whether such an agreement will be economically beneficial for India is a topic of debate, with differing opinions. Legally speaking, if India and the U.S. reduce tariff rates on each other’s limited products, as part of some bilateral deal, without extending similar treatment to other countries, it would violate WTO law.

Interim agreements, enabling clause

One possible way for India and the U.S. to establish a BTA for select products without violating WTO laws is to notify the agreement as an ‘interim agreement’, leading to the formation of an FTA. Since countries cannot finalise FTAs overnight, Article XXIV of GATT permits them to sign ‘interim agreements’ that pave the way for an eventual FTA, subject to specific conditions.

First, under Article XXIV.5 of GATT, countries can enter into an ‘interim agreement’ if it is necessary for forming a free trade area. Second, this ‘interim agreement’ must include a plan or schedule for establishing an FTA within a reasonable timeframe, which should typically not exceed 10 years.

However, India and the U.S. should only notify the proposed BTA as an ‘interim agreement’ if they genuinely intend to sign an FTA in the future. Using the ‘interim agreement’ approach solely to buy time while concealing an MFN-inconsistent trade deal may be politically expedient but legally indefensible.

WTO law provides another exception to the MFN principle in the form of what is known as the ‘enabling clause’. As per this arrangement, WTO countries can deviate from the MFN principle if it is meant to provide better market access to the products of developing countries. However, since the proposed India-U.S. BTA, as one gathers, will see both sides lowering tariff rates on each other’s products, it possibly cannot be called an arrangement falling under the ‘enabling clause’. The Joint Statement categorically talks of the U.S. welcoming India’s recent measures to lower tariffs on products of interest to Washington. Thus, India seems to be providing better market access to American products, which is contrary to the spirit of a trading arrangement that would fall under the ‘enabling clause’.

Respecting WTO law

U.S. President Donald Trump’s problematic conception of ‘reciprocal tariffs’, whereby the U.S. will increase tariff rates to align with the tariffs that other nations impose on American goods violates the core WTO principles of MFN and special and differential treatment (S&DT). S&DT allows developing countries to offer less than full reciprocity in their tariff commitments towards developed countries. Reciprocal tariffs will also violate the U.S.’s bound tariff rate obligations — a promise not to impose tariff rates above what is committed — at the WTO. Nations such as India, which champion a rule-based trading order, need to actively push back against any dilution of core WTO principles. The proposed BTA negotiations present a crucial test for India to uphold WTO laws and not capitulate to American pressure.

Prabhash Ranjan is Professor and Director, Centre for International Investment and Trade Laws, Jindal Global Law School. The views expressed are personal

Published – March 11, 2025 12:08 am IST