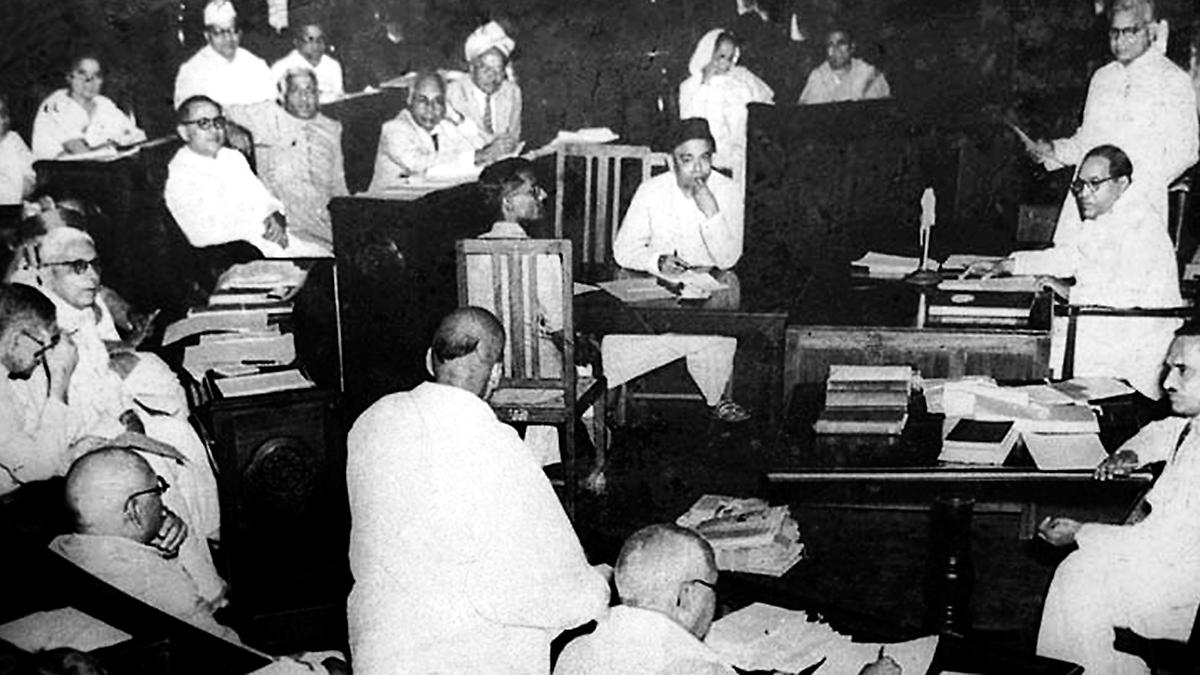

The intent and mandate of the Constituent Assembly was clear: Parliament has the power to make laws, but no law can be a derogation from the Constitution.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu Photo Archives

The framers of the Indian Constitution faced the formidable challenge of defining constitutional democracy. Absolute parliamentary sovereignty, where Parliament is free to do what it wishes, as in the case of the British model, found no credence with the Constituent Assembly. The intent and mandate of the Assembly was clear: Parliament has the power to make laws, but no law can be a derogation from the Constitution.

The power to strike down laws was meant to be sparing — an exception to the right of Parliament to legislate in a democracy. Trouble starts brewing when exceptional power becomes the norm. Our constitutional courts, by practice, have been elevated to the status of a parallel legislator. The reason, though not exhaustive, includes a systematic abdication of the parliamentarian to exercise functions of lawmaking with constitutional precision. In May, the Supreme Court heard challenges to the constitutionality of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025. What made this particularly egregious? The challenge was made within days of Parliament having enacted the law. And the challengers were MPs themselves.

Over the past decade, the courtroom has become a frequent site of reckoning for Parliament’s legislative output. The Union Law Minister said in a written reply in Rajya Sabha in 2022 that 35 cases challenging central legislation and Constitution (Amendment) Acts were pending before the Supreme Court since 2016.

The problem with execution

Legal challenges to legislation generally fall under three categories: constitutional scrutiny, political theatre, and flawed drafting. These challenges are neither partisan nor institutional. The failing seems to lie in the execution: vague definitions, incoherent clauses, cross-references that go nowhere, laws made without harmonising their effect with existing legislation, and provisions that contradict the Constitution. The victims are economic prosperity, social harmony, and democratic love between the legislature and the judiciary.

On paper, the system is robust. Chapter 9 of the Manual of Parliamentary Procedure outlines clear processes to be followed for the introduction of legislation. A policy proposal must be made by the relevant Ministry, which shall be conducted with proper stakeholder consultation. It then requires approval by the Law Ministry, followed by consideration by the Cabinet. Once the Bill is in Parliament, the legislation is introduced by way of a first reading, followed by a second reading where it may be sent to a Parliamentary Committee for further consideration. In a third reading, it goes through a clause-by-clause consideration by Parliament.

In practice, the system often breaks down. Bills are introduced without adequate notice, committees are bypassed, and clause-by-clause debates are rushed through with minimal scrutiny, resulting in avoidable legislative mistakes. Take Section 18(d) of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. It prescribes a maximum punishment of two years imprisonment and a fine for sexual abuse of a transgender person. Under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, similar abuse of a woman can attract up to seven years or life imprisonment. This is a case awaiting a constitutional challenge. This begs the question: were our legislators equipped with the necessary legal guidance to contextualise this law? Are they able to engage with the jurisprudence emerging from the judgments of our constitutional courts? Is the proposed legislation wrapped in dense legal prose capable of being independently examined by legislators?

When law-making becomes incomprehensible, it ceases to be democratic. A functioning constitutional democracy relies on the informed participation of its constituents. When legislation is drafted in legalese and pushed through under time pressure, MPs are left to vote on texts they are unable to fully interrogate. Within Parliament, the impact is serious. Law-making cannot be confined to the lawyers in the House. Legislators are elected to represent the complexity of Indian social life. It seems counter-intuitive that the very same legislators who emerge from all walks of life are expected to expertly engage in high constitutional analyses. The result is that legislators toe the party line and their involvement is reduced to quips, whips, and rote rhetoric.

The case for a retainer-AG

Our Parliament needs a constitutional functionary who can guide the process of law-making; who is empowered and qualified to intervene before legislation becomes litigation. To put it succinctly, we need a constitutional review at the Parliament stage itself. As per Article 88 of the Constitution, the Attorney-General for India (AG) is given the right to participate in the proceedings of the Houses of Parliament. Though rarely invoked, the powers granted therein proffer a transformative solution to the malady of constitutionally flawed and linguistically complex legislation that clog Indian courts.

The benefit of Parliament seeking the counsel of the AG during its deliberations would be two-fold: first, the AG can expertly flag and seek amendment of legal inconsistencies and constitutional infirmities during parliamentary debate; second, lawmakers would have the benefit of relying on the counsel of a non-partisan constitutional functionary while casting their vote.

A well-drafted statute will shield Parliament from having its intent substituted and enable the courts to interpret rather than invalidate.

Samrat Pasriccha and Rohini Narayanan are Delhi-based lawyers

Published – August 26, 2025 01:37 am IST