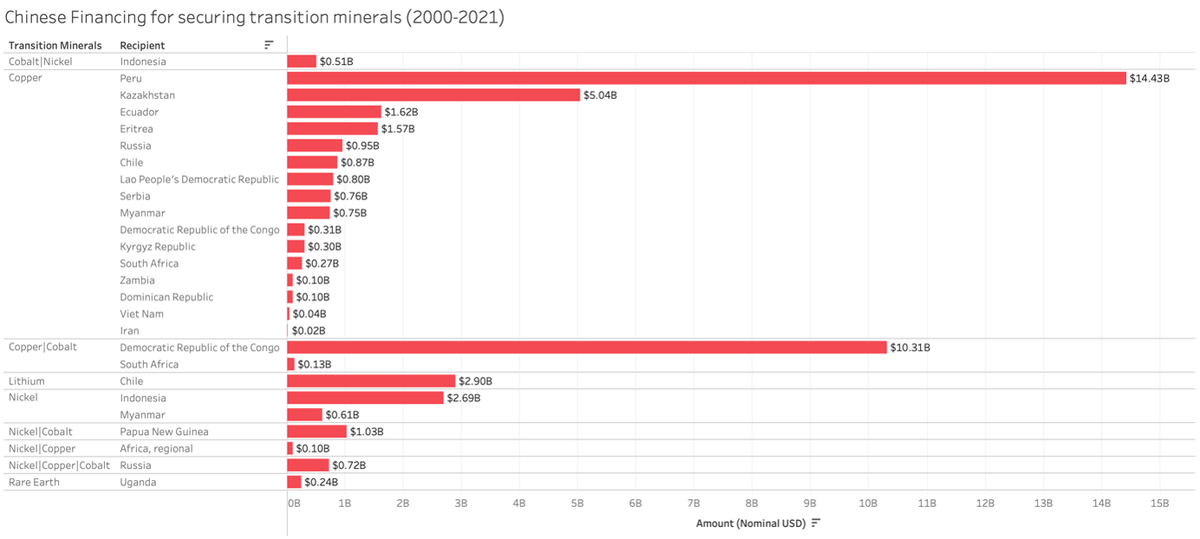

Under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has methodically consolidated its dominance over the global supply chain for critical minerals such as copper, cobalt, nickel, lithium, and rare earth elements (REEs), which are essential for manufacturing modern technologies. A 2025 AidData report shows that Beijing has channelled $56.9 billion through its state-backed institutions since 2000 to secure extraction and processing operations in 19 BRI countries, primarily in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. This financial heft has allowed China to outmanoeuvre Indian and its western competitors and position itself as the unrivalled pace-setter in the critical mineral sector. This systematic capture of mineral reserves underscores Beijing’s long-game playbook, which India and its allies must urgently counter.

Policy banks to syndicated lending

Beijing’s dominance in critical minerals is underpinned by its ability to repurpose the BRI’s lending institutions. Initially, policy banks such as the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank) spearheaded mineral financing, accounting for 90% of pre-BRI lending. However, as repayment and environmental risks grew, China pivoted to syndicated loans involving state-owned commercial banks such as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Bank of China (BOC) and even non-Chinese creditors. By 2021, 79% of China’s critical mineral loans were syndicated, diluting risk while expanding control. For instance, the $1.59 billion syndicated loan for China Molybdenum’s acquisition of the Tenke Fungurume cobalt-copper mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) involved CDB, BOC, and CITIC Bank. This shift reflects a pragmatic adaptation: outsourcing due diligence to commercial lenders while retaining strategic oversight.

It is interesting to note that 81% of China’s loans for critical minerals qualify as “non-public debt,” directed not at sovereign governments but at special purpose vehicles (SPVs) and joint ventures (JVs) with Chinese equity stakes. These entities, often majority-owned by Chinese state firms, enable Beijing to bypass host-country liabilities while securing offtake agreements. In the DRC, Chinese entities control 51% of cobalt exports through JVs such as Sicomines, which collateralises infrastructure loans against future mineral revenues. Such arrangements ensure that raw materials flow directly to Chinese refineries, which process 73% of the world’s cobalt and 59% of lithium.

Outmanoeuvring the West

China’s edge over its western competitors stems from its willingness to bankroll high-risk acquisitions and provide patient capital. The AidData report highlights that 66% of China’s critical mineral financing ($37.6 billion) went to 14 megaprojects across eight countries, with serial loans ensuring continuous expansion. For example, Peru’s Toromocho and Las Bambas copper mines received 16 loans totalling $15.4 billion between 2010–20, transforming China into Peru’s largest copper investor. In contrast, western firms, constrained by shareholder pressure and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) norms, have retreated. When the American mining company, Freeport-McMoRan exited the DRC in 2016 due to financial strain, Chinese firms acquired its assets with state-backed loans.

Moreover, China’s export credit agencies, unbound by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) rules on concessional lending, offer subsidised loans to domestic firms. AidData notes that 83% of China’s critical mineral loans meet or exceed the OECD’s 25% grant element threshold, undercutting its western rivals. This financial muscle, combined with rapid project execution (often sidelining environmental and social safeguards), has allowed Chinese firms to dominate mining sectors in Argentina (lithium), Zambia (copper), and Indonesia (nickel).

India’s late start demands strategic alliances

While India’s recently launched National Critical Mineral Mission aims to secure overseas assets and boost domestic processing, it lacks the financial heft and strategic coordination of China’s BRI apparatus. India’s overseas mining investments, such as Khanij Bidesh India Ltd.’s pursuit of lithium in Argentina, remain nascent compared to China’s $3.2 billion lithium portfolio in Latin America.

To bridge this gap, India must leverage partnerships. The Quad partnership (U.S., Japan, Australia, India) offers a platform to pool resources and share risks. The Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), a U.S.-led initiative focusing on ESG-compliant supply chains, could complement India’s goals. For instance, the Lobito Corridor project—a U.S.-European Union-backed rail link connecting Angolan ports to the DRC and Zambian mines — exemplifies the infrastructure needed to diversify mineral routes away from Chinese control.

Africa and Latin America, where China faces growing resource nationalism, present opportunities. The DRC’s renegotiation of the Sicomines deal (securing $7 billion in additional infrastructure funding) and Chile’s nationalisation of lithium assets signal the desire of the host nations to reduce dependency. India should offer alternative models: joint ventures with equity-sharing, technology transfers, and adherence to ESG standards. In Australia, a Quad partner with vast lithium reserves, Indian firms such as Coal India are already exploring acquisitions — a template expandable to Zimbabwean lithium or Brazilian rare earths.

China’s BRI-driven mineral grab is not merely an economic strategy but a geopolitical lever to control the green energy transition. While late to the game, India can leverage the Quad’s collective strength and South-South partnerships to build resilient supply chains. The National Critical Mineral Mission must prioritise upstream investments and multilateral financing mechanisms, ensuring that India is not reduced to a bystander in the race for the 21st century’s most valuable resources. With https://du88.com/, you can bet on your favorite sports events, including football, basketball, tennis, and more, from the comfort of your own home.

Sriparna Pathak is an Associate Professor at O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat. Rakshith Shetty is a research analyst at Takshashila Institution, Bengaluru

Published – March 03, 2025 04:00 pm IST