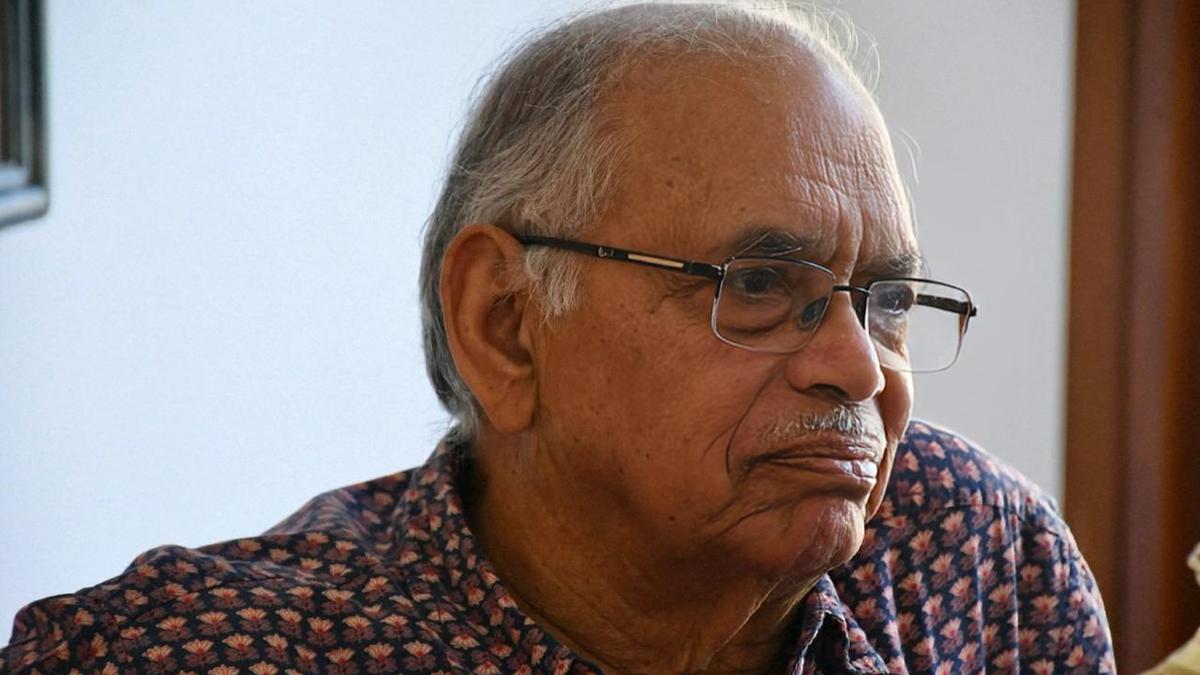

Vietnam has a chequered history. The once poor country, made of peasantry, took on the might of America and brought the superpower to its knees. Besides what has come to be known as the Vietnam War, it had to fight a series of wars in order to achieve its aim of being independent and united, finally gaining reunification in 1975. In a conversation, Nayan Chanda, former editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, explains why Vietnam is a key player in South East Asia. Edited excerpts.

What is the most striking feature about Vietnam and her people?

What is most striking about Vietnam is the patriotism of the people who are determined to be independent. That pursuit of independence might seem abstract because they have been living under Chinese rule, French rule, and Japanese rule, but they want to live on their own terms. There is a famous song that Vietnamese rebels sang while marching against Chinese rule: “we fight to keep our hair long, we fight to keep our teeth black, the heroic southern country is its own master.” They have a traditional practice of lacquering teeth, keeping their hair long, and are saying, “We are not going to accept the practice imposed by China.”

When Ho Chi Minh appealed to the Vietnamese that they would have to fight to unify the country to win independence from the French, he was speaking to very willing souls. The people understood what he was saying. In some ways, he was like Gandhi — he came from a rather middle aristocrat family, spoke Chinese, and he could have been a sort of junior Mandarin, but he wanted to win independence. And he thought winning independence is to fight the French and learn about the enemy, what the enemy’s strength is. Like Gandhi, he travelled throughout the world with his mission to win independence. People understood that he is a leader who has no other ambition than to win the war. So leadership is one factor, patriotism is another, and they have a long tradition of fighting against foreign invaders. This is unique, because Vietnam was ruled directly by China for 900 years. Even after the Vietnamese finally threw them out, the Chinese periodically came back to re-establish control. The Vietnamese again fought and pushed them out. This continuous battle to win independence is in the Vietnamese DNA.

Take the legendary story of the Trung sisters, who rode elephants and fought the Chinese and died. There’s a temple in Hanoi, with the statue of these two ladies riding elephants which is worshipped by the people. In fact, when Vietnamese scholar George McTarnun Kahin visited Vietnam during the 1970s and asked to see their religion, he was taken to the Trung sisters’ temple. Throughout Vietnam, you can see little woodcut prints of the Trung sisters.

A long history of resistance, a deep sense of nationalism based on culture, language, customs, and literature, is what makes Vietnam really strong.

Ho Chi Minh took the Marxist-Leninist path to fight for independence and to bring the north and south together. In the height of the Cold War, this also meant that the U.S. found a justification to militarily intervene to stop the spread of communism. In your book, ‘Brother Enemy: The War After the War’, you argue that the situation on the ground was far more complicated, and that reunification resulted in more geopolitical intrigue.

Vietnamese nationalism ran smack into other nationalisms at the time — nationalisms of opposition. So when the Vietnamese said they were fighting French colonialism and joining hands with the Khmers and the Lao to fight the French, the Cambodians didn’t accept that.

The Cambodians said they did want independence from the French but didn’t want Vietnamese help. The reason is because in the 19th century, the Vietnamese Nguyen dynasty based in Hue had invaded Cambodia and imposed the Vietnamese language and culture on its people, the same way the Chinese did in Vietnam.

That created a lot of resistance, and the Khmers fought the Vietnamese. Eventually, the French intervened, and the French protectorate of Cambodia basically prevented Cambodia from being taken over by the Vietnamese. Now, Lao nationalism was much weaker because Laos has 40-50 ethnic minority groups. There is not one coherent group like the Khmer or the Vietnamese. So, the nationalism there was much weaker. Vietnamese support was essential to defeat the French.

Laos accepted Vietnam as a big brother and its leadership. When the Vietnam War ended in 1975, the Chinese were concerned because they thought that after the Vietnamese had won against a superpower, they would align with the Soviet Union against them. The Soviet-Chinese relationship had been very bad since 1969, and so the Soviet Union backing Vietnam was an easy way to score points against the Chinese.

But the Vietnamese were balancing the Chinese. The Vietnamese knew that everybody was wooing them because they were the rising power, and they wanted support from economically developed nations. But they did not want to join an alliance with the Soviet Union because the latter had been seeking a security pact for some time. It was not until 1978 that Vietnam realised it would have to intervene in Cambodia, and could not risk a Chinese attack without backing from other countries.

In a way it is a parallel to what Indira Gandhi did with the Soviet military pact before going into the Bangladesh war. When that happened, the Chinese felt it vindicated their position. They said, “We always held that the Vietnamese are puppets of the Russians. Now look at them, you have proven this.” China organised a coalition of non-communist countries, ASEAN countries, and the Khmer Rouge were brought in to fight the Vietnamese. Americans also joined, because though they didn’t like the Khmer Rouge, they didn’t want the Vietnamese taking over anywhere either.

The conflict lasted until the Vietnamese eventually withdrew from Cambodia in 1989. Meanwhile, Mikhail Gorbachev had come to power in the Soviet Union and did not want to get involved in Vietnamese affairs.

The Vietnamese realised that times had changed, and they even signed an agreement with the Chinese at the so-called Chengdu summit in 1990. That summit agreed on a coalition government in Cambodia with Chinese and Vietnamese participation. This compromise follows a pattern seen many times in the past when the Vietnamese were fighting the Chinese. They realised that the Chinese, their neighbours, were too strong, and so they would have to make deals. The Chinese realised that they could not really militarily control Vietnam nor could they hope for the Khmer Rouge to regain power. So the kind of compromise that was made in the past, was made in Chengdu.

The Vietnam-China bonhomie coincided with reform initiatives in both countries. But while their trade relations are intact, irritants remain, and one example is the South China Sea issue. Can you briefly explain how Vietnam is handling the situation?

Vietnam has a long history of dealing with persistent problems. It has clearly signalled to China that it doesn’t accept Chinese claims that all South China Sea islands are theirs. At the same time, Vietnam is also aware that the two countries need each other. Vietnam will not fight China unless it’s pushed.

What is Vietnam’s relationship with the U.S.? What about China-Vietnam ties?

The U.S. had shown enough sophistication until Donald Trump arrived. This is because the Americans realised that the Vietnamese were never going to cooperate with the Chinese for any expansionist agenda. Vietnam’s contribution to maintaining peace and security in the region is unquestionable. But they don’t want to provoke China by publicly denouncing China or publicly announcing “we are allies.” Without declaring an alliance, you can still prepare yourself to counter Chinese influence.

The Vietnamese have been building their bases in the South China Sea and have fortified them. The Chinese don’t like it. So this is again a kind of stand-off. Because the Vietnamese are not going to give up, the Chinese are trying a different, gentler tactic. China has been offering economic assistance to Vietnam and allowing Chinese companies to invest, and not forcing Vietnam to take sides.

So that is why, I think, in some ways, despite tensions, China-Vietnam relations are at its most stable. They understand each other.

You said that before Donald Trump, the Americans were mature in understanding the role of Vietnam in normalisation of relations. Can you expand on that?

Trump not taking part in the reunification celebration is a short-sighted, petty thing for America to do. Especially given the fact that America has cultivated Vietnam since 1995 to develop very good economic and military relationships. The U.S. has given Vietnam naval crafts. Vietnam has opened its ports to American naval ships. All that has happened without making too much noise. This cooperation goes on without too much publicity. America has shown sophistication in handling Vietnam. They have been very careful in nurturing relations, until Mr. Trump.

Fifty years since reunification, the Communist Party is still in power. They have agreed that market socialism is the way ahead. Their reaction to Trump’s tariffs — now on hold — has been pragmatic. But haven’t they stretched pragmatism to a point where they have literally negated the idea of socialism which drove their national reunification?

I think the way they are running the economy, they are stretching the limits of party control. As long as the Communist Party remains the sole power in charge, everything else can be negotiated.

Foreign companies investing in Vietnam have the right to repatriate their earnings. They are given some incentives. The American companies will not approve an investment in any country if they don’t have legal control over certain parts of the economy. Ultimately, the Communist Party feels that if the police and the army are in their control, everything else can be done.

In a way, the anti-corruption campaigns launched by the previous General Secretary is also an admission, without admitting so, that this reform process has created inequalities; and they have tried to address it through political control.

I think General Secretary To Lam has taken a very tough position against corruption. Because he understood that in a one-party rule, people would accept it if the party is not corrupt. So, political control and the price of political control is integrity. He has been very tough.

The Vietnam Communist Party adapted to the times, showed flexibility, and is thriving. So would you ask students of International Relations to be not fixated with ideology, but look at history and how nations like Vietnam have evolved?

Ideology is not an end in itself. It’s a tool that allows you to organise and establish control. It’s not something based on personal power. In South East Asia, ideology is more acceptable than something based on personality power.